Black Notebook

There’s a small black three-ring notebook Mom kept in one of the cardboard drawers that used to be in Granpa’s basement. When Granpa died Mom brought everything from his house in Denver to our house in San Diego. The cardboard drawers, his digital alarm clock, all the books from the shelves, even an unopened bottle of Canada Dry Club Soda. Everything means everything. There were lamps and vases and sheets and towels and the killer rug , the one that would slip and slide on the hardwood floor sending me skating across the room where Gramma’s hospital bed had been. The rug would fling me into the writing desk on the far wall.

That desk is where the notebook had been until Mom brought it to San Diego and stashed in the cardboard drawer with the crinkly edged black and white photos and the tiny metal cars from an ancient board game and a shaving mug with a stag on the side. I was allowed to take out the photos and the cars and even the mug if I wanted to, but what I loved was the notebook. It smelled old and the yellowed pages were covered in fancy writing. I tried to copy the writing. My left-handed penmanship was improved over the days when all of my J’s were backward but it still wasn’t very good. Gramma had a funny way of making capital N’s that look like the pi sign: two sticks with a hat. Her capital M’s were three sticks with a hat. I’d never seen anything like it.

This wasn’t Gramma’s diary. There were no intimate details scrawled in black ink across these pages. Those pages, if they ever existed, were long gone. The pages of this notebook are filled with poetry. Not her poetry, nothing she’d written herself, no grand window into her soul. This was where she’d copied the works of William Shakespeare and Rupert Brooke, some in part, some in full. She also transcribed a poem by Lydia A Coonley. Ever heard of her? Yeah, me neither. Coonley was a suffragette who published Under the Pines and Other Verses in 1895, her only book. Gramma liked one of them enough to copy it into her notebook. One obscure poem from all the things she read. All these years later I have to wonder how they came together.

This is what I see in my mind’s eye:

Gramma pulled out a chair from the dining table and dragged it over to the writing desk where she’d already lit the wick in the oil lamp and set out her pen and inkwell. Heavy curtains have been drawn, not against prying eyes but the November chill. The inkwell is a glass jar wrapped in leather with a metal lid. The pen is bright black. It has no clip so it rests between the inkwell and the notebook so it won’t roll onto the floor. Under the notebook is a copy of Kipling’s The Years Between that Gramma borrowed from a neighbor. She wants to copy “The Son’s of Martha” but it’s cold and the desk is too far from the fire. Her fingers could get numb before she finishes so she’s chosen one stanza. She arranges a cushion that has been embroidered with violets and sits down opening the book to the page she has marked with a lavender ribbon.

This is how I imagine the black notebook came to be filled. Odds and ends from borrowed books and clippings from magazines reproduced in her hand between these covers.

Maybe it is a window into my mother’s mother. These were things she collected for herself, not to share with others. This black notebook made the journey from Grand Junction to Los Angeles back to Denver. Gramma saved it for at least fifty years until she died in 1977. Granpa never moved it and when he died in 1984 Mom brought it back to California.

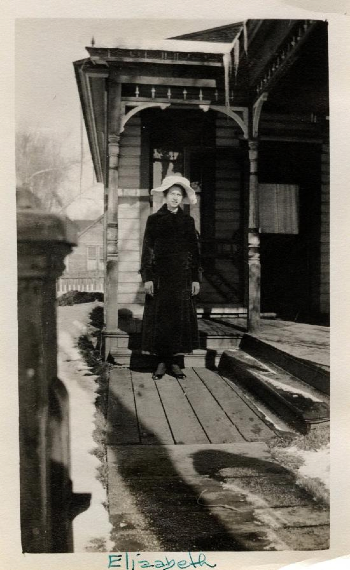

Mom gave it to me several years ago along with some recipes and letters and other odds and ends. So now I’m left with these papers to piece together who Gramma was, not through the stories and photos and memories of others, but with what has been left for me to discover on my own.