Universal Studios StarWay

Daily Booth

Hollywood Hills, CA

Just got home. Out too late. Gonna be a rough morning later.

Daily Booth

Hollywood Hills, CA

You know how sometimes you think you're on track and everything's hunky dory but then you look around and realize that maybe you're not.

That's what tomorrow is for, right?

Music Swims Back to Me

Music Swims Back to Me

by Anne Sexton

Wait Mister. Which way is home?

They turned the light out

and the dark is moving in the corner.

There are no sign posts in this room,

four ladies, over eighty,

in diapers every one of them.

La la la, Oh music swims back to me

and I can feel the tune they played

the night they left me

in this private institution on a hill.

Imagine it. A radio playing

and everyone here was crazy.

I liked it and danced in a circle.

Music pours over the sense

and in a funny way

music sees more than I.

I mean it remembers better;

remembers the first night here.

It was the strangled cold of November;

even the stars were strapped in the sky

and that moon too bright

forking through the bars to stick me

with a singing in the head.

I have forgotten all the rest.

They lock me in this chair at eight a.m.

and there are no signs to tell the way,

just the radio beating to itself

and the song that remembers

more than I. Oh, la la la,

this music swims back to me.

The night I came I danced a circle

and was not afraid.

Mister?

To Thomas Moore

(Lord Byron)

To Thomas Moore

My boat is on the shore,

And my bark is in1 the sea;

But, before I go, Tom Moore,

Here's a double health to thee!

Here's a sigh to those who

love me,

And a smile to those who

hate;

And, whatever sky's above

me,

Here's a heart for every fate.

Tho2 the ocean roar around

me,

Yet it still shall bear me on;

Tho3 a desert should surround

me,

It hath springs that may

be won.

Were't the last drop in

the well,

As I gasped4 upon the brink,

Ere my fainting spirit fell,

Tis to thee that I would drink.

With that water, as this wine,

The libation I would pour

Should be -peace with thine and mine,

And a health to thee, Tom Moore!

1 Bryon used “on”

2 & 3 Byron used “Though”

4 Byron used “gasp'd”

Summer 1955

Still hanging with my sisters. The greaser reunion rages on!

Kathy and Beth from the summer of 1955.

Yup. They're OLD!!!

When We Two Parted

When We Two Parted

by George Gordon, Lord Byron

When we two parted

In silence and tears,

Half broken-hearted

To sever for years,

Pale grew thy cheek and cold,

Colder thy kiss;

Truly that hour foretold

Sorrow to this.

The dew of the morning

Sunk chill on my brow—

It felt like the warning

Of what I feel now.

Thy vows are all broken,

And light is thy fame:

I hear thy name spoken,

And share in its shame.

They name thee before me,

A knell to mine ear;

A shudder comes o'er me—

Why wert thou so dear?

They know not I knew thee,

Who knew thee too well—

Long, long shall I rue thee,

Too deeply to tell.

In secret we met—

In silence I grieve,

That thy heart could forget,

Thy spirit deceive.

If I should meet thee

After long years,

How should I greet thee?—

With silence and tears.

Lad April

Lad April

April is no lady;

April is a boy,

Wearing torn green trousers

Made of corduroy!

Whistling thru the woodland

Cheerily he goes,

Nothing but the brown dust

covering his toes.

Lad, he cuts a sling shot

Out of tough green wood,

Shoots at all the squirrels

In the neighborhood.

Clambers in the treetops,

Swings across the air,

Never hurts a robin

or a bluebird there.

April goes a-fishing

with a small green rod,

No one else goes with him-

Only, maybe, God.

Kathryn Wood -

Vacation, All I Ever Wanted

I'm hanging out with Beth and Kathy at Grauman's Chinese Theater right now.

Or maybe exploring Madame Tussaud's.

Beth's never seen the Walk of Fame.

More on all that soon.

Any way you slice it,

the Greaser Reunion is in full swing

and I am hanging out with my sisters.

Can't seem to get my mind off of you

Back here at home there's nothin' to do

Now that I'm away

I wish I'd stayed

Tomorrow's a day of mine

That you won't be in

When you looked at me

I should've run

But I thought it was just for fun

I see I was wrong

And I'm not so strong

I should've known all along

That time would tell

A week without you

Thought I'd forget

Two weeks without you and I

Still haven't gotten over you yet

Vacation

All I ever wanted

Vacation

Had to get away

Vacation

Meant to be spent alone

Vacation

All I ever wanted

Vacation

Had to get away

Vacation

Meant to be spent alone

A week without you

Thought I'd forget

Two weeks without you and I

Still haven't gotten over you yet

Vacation

All I ever wanted

Vacation

Had to get away

Vacation

Meant to be spent alone

Vacation

All I ever wanted

Vacation

Had to get away

Vacation

Meant to be spent alone

Vacation

All I ever wanted

Vacation

Had to get away

Vacation

Meant to be spent alone

The Walrus and the Carpenter

The Walrus and the Carpenter

by Lewis Carroll

The sun was shining on the sea,

Shining with all his might;

He did his very best to make

The billows smooth and bright--

And this was odd, because it was

The middle of the night.

The moon was shining sulkily,

Because she thought the sun

Had got no business to be there

After the day was done--

"It's very rude of him," she said,

"To come and spoil the fun!"

The sea was wet as wet could be,

The sands were dry as dry.

You could not see a cloud, because

No cloud was in the sky:

No birds were flying overhead--

There were no birds to fly.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

"If this were only cleared away,"

They said, "it would be grand!"

"If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year.

Do you suppose," the Walrus said,

"That they could get it clear?"

"I doubt it," said the Carpenter,

And shed a bitter tear.

"O Oysters, come and walk with us!"

The Walrus did beseech.

"A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach:

We cannot do with more than four,

To give a hand to each."

The eldest Oyster looked at him,

But never a word he said:

The eldest Oyster winked his eye,

And shook his heavy head--

Meaning to say he did not choose

To leave the oyster-bed.

But four young Oysters hurried up,

All eager for the treat:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat--

And this was odd, because, you know,

They hadn't any feet.

Four other Oysters followed them,

And yet another four;

And thick and fast they came at last,

And more, and more, and more--

All hopping through the frothy waves,

And scrambling to the shore.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Walked on a mile or so,

And then they rested on a rock

Conveniently low:

And all the little Oysters stood

And waited in a row.

"The time has come," the Walrus said,

"To talk of many things:

Of shoes--and ships--and sealing-wax--

Of cabbages--and kings--

And why the sea is boiling hot--

And whether pigs have wings."

"But wait a bit," the Oysters cried,

"Before we have our chat;

For some of us are out of breath,

And all of us are fat!"

"No hurry!" said the Carpenter.

They thanked him much for that.

"A loaf of bread," the Walrus said,

"Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed--

Now if you're ready, Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed."

"But not on us!" the Oysters cried,

Turning a little blue.

"After such kindness, that would be

A dismal thing to do!"

"The night is fine," the Walrus said.

"Do you admire the view?

"It was so kind of you to come!

And you are very nice!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"Cut us another slice:

I wish you were not quite so deaf--

I've had to ask you twice!"

"It seems a shame," the Walrus said,

"To play them such a trick,

After we've brought them out so far,

And made them trot so quick!"

The Carpenter said nothing but

"The butter's spread too thick!"

"I weep for you," the Walrus said:

"I deeply sympathize."

With sobs and tears he sorted out

Those of the largest size,

Holding his pocket-handkerchief

Before his streaming eyes.

"O Oysters," said the Carpenter,

"You've had a pleasant run!

Shall we be trotting home again?'

But answer came there none--

And this was scarcely odd, because

They'd eaten every one.

Something to Think About

Something to Think About

“Ah!” sighed the World, as he

turned in bed

With a pillow of cloud for

his poor old head

And lowered the roller

shade of Night

And blew out a star that

shone too bright–

“The year is gone with his

toil and strife,

The storm and surge of the

tide of life.

The crazy brawl of the

human breed,

And I’ll rest at last – for

it’s rest I need!”

Down came an elf through the

moonlight pale

From the Milky Way

on a comet’s tail;1

He turned up the lamps

that were burning low

And prodded the World

with a small pink toe.

“Get up!” he cried, “That’s

enough for you!

There’s a heap of things for

a World to do!

“There are wounds to bind,

there’s a map to fix,

There’s a beautiful tangle

of politics,

There are towns to build

there are wheels to

start

There’s a load of crowns

for the junkman’s cart

There’s an ancient fraud in

a

brand new dress,

There are lovely riddles for

men to guess,

There are dreams to dream

There are heights to climb,

And you can’t lie there and

waste your2

time!”

So the World rose up

with a plaintive groan,

Stubbing his toe on a

tumbled throne,

To round the Sun on his

wonted track -

The deep-grooved trail of the

Zodiac,

That way of sorrows and

joys

and aches,

Of noble efforts and fool

mistakes.

But it’s good for the poor

old World, at that;

For a drowsy Planet gets

much too fat.

-

Arthur Guiterman:

A Ballad-Maker’s Pack

New Year,

1919

by Arthur Guiterman

from A Ballad-Maker’s Pack

1 Gramma

left out this stanza between “comet’s tail” and “He turned up”:

His

traveling-bag, in letters clean

Was

marked, “A.D. Nineteen-nineteen.”

2 Guiterman used “my”.

Black Notebook

There’s a small black three-ring notebook Mom kept in one of the cardboard drawers that used to be in Granpa’s basement. When Granpa died Mom brought everything from his house in Denver to our house in San Diego. The cardboard drawers, his digital alarm clock, all the books from the shelves, even an unopened bottle of Canada Dry Club Soda. Everything means everything. There were lamps and vases and sheets and towels and the killer rug , the one that would slip and slide on the hardwood floor sending me skating across the room where Gramma’s hospital bed had been. The rug would fling me into the writing desk on the far wall.

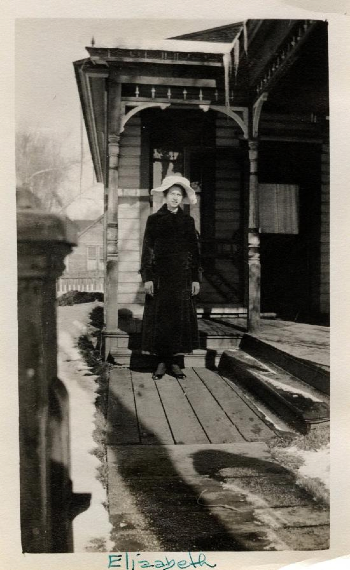

That desk is where the notebook had been until Mom brought it to San Diego and stashed in the cardboard drawer with the crinkly edged black and white photos and the tiny metal cars from an ancient board game and a shaving mug with a stag on the side. I was allowed to take out the photos and the cars and even the mug if I wanted to, but what I loved was the notebook. It smelled old and the yellowed pages were covered in fancy writing. I tried to copy the writing. My left-handed penmanship was improved over the days when all of my J’s were backward but it still wasn’t very good. Gramma had a funny way of making capital N’s that look like the pi sign: two sticks with a hat. Her capital M’s were three sticks with a hat. I’d never seen anything like it.

This wasn’t Gramma’s diary. There were no intimate details scrawled in black ink across these pages. Those pages, if they ever existed, were long gone. The pages of this notebook are filled with poetry. Not her poetry, nothing she’d written herself, no grand window into her soul. This was where she’d copied the works of William Shakespeare and Rupert Brooke, some in part, some in full. She also transcribed a poem by Lydia A Coonley. Ever heard of her? Yeah, me neither. Coonley was a suffragette who published Under the Pines and Other Verses in 1895, her only book. Gramma liked one of them enough to copy it into her notebook. One obscure poem from all the things she read. All these years later I have to wonder how they came together.

This is what I see in my mind’s eye:

Gramma pulled out a chair from the dining table and dragged it over to the writing desk where she’d already lit the wick in the oil lamp and set out her pen and inkwell. Heavy curtains have been drawn, not against prying eyes but the November chill. The inkwell is a glass jar wrapped in leather with a metal lid. The pen is bright black. It has no clip so it rests between the inkwell and the notebook so it won’t roll onto the floor. Under the notebook is a copy of Kipling’s The Years Between that Gramma borrowed from a neighbor. She wants to copy “The Son’s of Martha” but it’s cold and the desk is too far from the fire. Her fingers could get numb before she finishes so she’s chosen one stanza. She arranges a cushion that has been embroidered with violets and sits down opening the book to the page she has marked with a lavender ribbon.

This is how I imagine the black notebook came to be filled. Odds and ends from borrowed books and clippings from magazines reproduced in her hand between these covers.

Maybe it is a window into my mother’s mother. These were things she collected for herself, not to share with others. This black notebook made the journey from Grand Junction to Los Angeles back to Denver. Gramma saved it for at least fifty years until she died in 1977. Granpa never moved it and when he died in 1984 Mom brought it back to California.

Mom gave it to me several years ago along with some recipes and letters and other odds and ends. So now I’m left with these papers to piece together who Gramma was, not through the stories and photos and memories of others, but with what has been left for me to discover on my own.